Without salt, our food would taste pretty bland but it’s not uncommon to find yourself reprimanded for adding salt at the table. Are we actually eating too much salt and do we need to restrict our intake and perhaps our enjoyment of food? The answer is not that straightforward and indeed, may surprise you.

If you’re confused about salt, unclear about what we need it for, not sure if you’re eating too much and conversely, whether you’re eating enough….read on!

Many processed foods and ready meals are notoriously high in salt and whilst many will claim to be ‘delicious’ and ‘flavoursome’, more often than not, this is down to the high salt content of the meal, rather than the quality and quantity of full-flavoured ingredients.

When you cook from scratch, it’s easy to control how much salt you add to your food. But when you opt for ready meals on a regular basis, not only do you lose this control, you also adjust your palate to expect a high salt taste. There is even a lot of hidden salt in foods that you would not always expect to be high in salt – for example, bread and breakfast cereals.

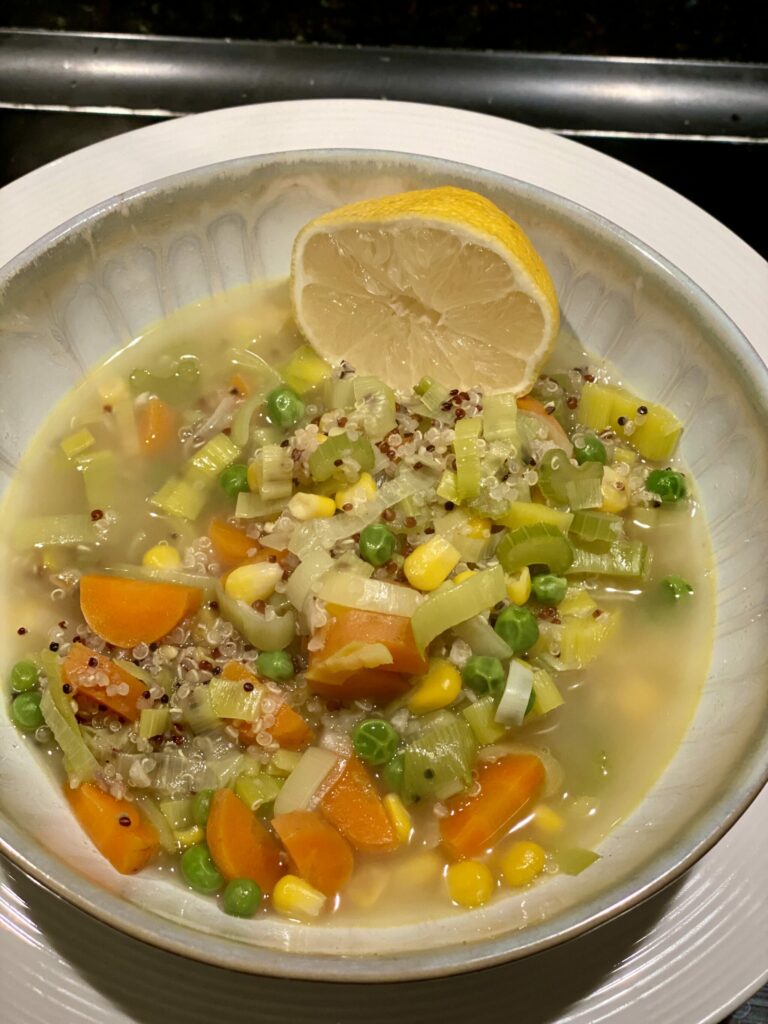

When you cook from scratch, it’s easy to control how much salt you add to your food

It takes around 10 days to adjust the taste buds, so it won’t be long before you are enjoying your meals with a more moderate amount of salt.

Are we really eating too much salt?

According to the UK National Health Service, the recommended maximum salt consumption is 6g per day, the equivalent of just one teaspoon.

A leading study by McMaster University recently published in The Lancet now shows an associated risk of cardiovascular disease only where the average intake is more than 5g of sodium per day – the equivalent of 1.5 to 2.5 teaspoons of salt. World Health Organisation advice cautiously recommends less than 2g of sodium as a preventative measure against cardiovascular disease. Furthermore, The American Heart Association recommends even less; 1.5g sodium per day for those at risk of heart disease.

This research found that not only was there no direct link between sodium intake and heart conditions such as heart attacks and strokes, but also an inversely related association was noted – that is, no increase in stroke and decreased cardiovascular events.

The study concludes that ‘there is no convincing evidence that people with moderate or average sodium intake need to reduce their sodium intake for prevention of heart disease and stroke’.

Whilst this may be encouraging news, it is important that we have a clear understanding of what ‘moderate’ or ‘average’ salt intake actually refers to and furthermore, how salt intake differs from sodium intake.

Salt vs Sodium

Salt is added to many foods, including bread, cakes and biscuits, to bring out the flavour and some foods can contain very high amounts of salt. To confuse the consumer, sometimes manufacturers will use sodium on the label instead of salt.

Many will know that the chemical name for salt is sodium chloride and as such contains both sodium and chloride.

Only around 40 per cent of the weight of salt contains sodium, so you will need to multiply this amount by 2.5 to establish the actual salt content.

Thus 2.4mg of sodium equates to around one teaspoon or 6g of salt per day; the UK government recommendation. Can you see how labels that only list sodium content can be misleading and you can easily find yourself eating excessive salt even though you’re consulting these food labels?

How important is salt to the body?

What is the role of salt in our body? It is in fact a crucial electrolyte that maintains the correct balance of fluids both within the cells and outside.

Along with potassium, sodium from salt will help to ensure that nerve transmission, muscle contractions and many other functions can take place. In other words, sodium is essential for the body to function.

The more sodium we have in our body, the more water it attracts and it is for this reason that excessive salt can cause high blood pressure (the more water your body retains in the blood, the more pressure within the body).

With high blood pressure, the heart has to work harder to ensure the blood is pumped around the body, causing increased strain on the arteries and organs in doing so. Thus, high blood pressure is considered a major risk factor for many health conditions including heart disease and stroke.

Studies do show that reducing sodium intake can lower blood pressure. A 2013 study involving 3230 participants reported a modest reduction in salt intake for 4 or more weeks did result in a significant fall in blood pressure, in both individuals with high and normal blood pressure.

However, when this study was undertaken, government recommendations were higher at around 9-12g per day whereas this has now been reduced to 6g per day, which the study recommended should become a long term target for population salt intake. On this basis, it seems that 6g per day would be an appropriate recommendation.

It’s not only a question of reducing your salt consumption…

Whilst reducing salt intake may reduce the risk factors for developing disease, it is not enough on its own. It will vary from individual to individual and can depend on a number of lifestyle factors, such as diet, smoking and exercise levels.

It can be surprisingly easy to unwittingly load up on your sodium intake. After all, if you’re dining out on pizza or a burger meal or many other take out choices, you are probably eating way more sodium, and therefore salt, than you realise.

How do we know we’ve had too much?

When you’ve eaten a highly salty meal, you’ll probably feel incredibly thirsty as your body struggles to maintain its fluid balance. Your body is alerting you that there isn’t enough water to support the amount of sodium in your body, so your brain will receive a signal that it needs more water.

Bloating and water retention are also common signs of eating excessive salt.

With too much sodium in the body, the fluid is forced out of the cells and into the blood to support these excessive levels. Bloating around the tummy area is most common, but you may also notice your fingers and toes to be a little more swollen.

Headaches can also be triggered after a high salt meal; as the blood vessels in the brain swell due to extra fluid from the cells, this can cause pain in the form of a headache.

How about too little salt?

While you will lose a modest amount of sodium throughout the day when you sweat or urinate, these will easily be replaced from the foods we eat, with a varied and balanced diet. However, if you overexert yourself, excessive sweating can lead to an excessive loss of sodium. Furthermore, you can then continue to reduce your sodium levels by drinking too much water (as can often be the case during an endurance exercise activity) and diluting its concentration.

Whilst this will be an extreme situation to find yourself in, it is worth noting the symptoms that this will trigger including nausea, vomiting, muscle cramps, lightheadedness in a mild situation. It is better to drink more steadily throughout the day rather than drinking large quantities in one go.

Do we need to eat more salt if we exercise more?

Many recommendations when it comes to exercise suggest that you need to replace sodium lost with sweat during exercise.

Indeed, many endurance athletes may also consume much larger quantities of salt or any other electrolyte supplements (many sports drinks claim to contain electrolytes) containing sodium during training and competition in the belief that they can help to improve performance. Researchers found that this in fact neither hinders nor helped performance.

Ensuring moderate sodium consumption is probably more advisable and athletes should be cautious if considering sodium supplements, in order to minimise other health risk factors.

Which salt?

With an array of salts now presented on the spice aisles, choosing a salt now requires more than a passing glance!

Pink Himalayan, sea salt, salt flakes, celery salt are just some of the names on offer and these have become fashionable alternatives to the original table salt that was once plain and simple to grab.

Whilst they can certainly sound more interesting and can be deemed less processed, do they actually offer any additional health benefits?

Table salt is the most common and is harvested from salt deposits underground. It’s highly refined to remove impurities and as a result, most of the trace minerals and elements have also been removed.

It will also contain an anti-caking agent to improve its appearance and flow. Some varieties will have iodine added as a preventative measure against iodine deficiency, which is often a problem in many communities, due to modern vegetable production methods and inadequate levels in the soil. A lack of iodine can lead to thyroid problems amongst other health issues.

Sea salt will be harvested from evaporated seawater and is usually unrefined and more coarse than table salt. Thus, it will contain some additional minerals such as potassium, zinc and iron, making it a slightly more nutritive choice. It also has a deeper flavour as a result.

When it comes to Himalayan salt, this is indeed harvested with minimal processing, in mines in the Himalayan mountains and is rich in numerous natural minerals and trace elements such as calcium, iron, potassium and magnesium, that the body needs.

Its pink colour is due to trace amounts of iron oxide or rust. As such, there’s perhaps a benefit in eating this more nutrient-rich salt, as opposed to a highly processed table salt, which is lacking in natural minerals. It is also lower in sodium.

In any case, it is worth bearing in mind that the mineral content in these salts is trace amounts and negligible when compared with the quantities found in food. It is more important that you consider the type you use to add taste and flavour rather than its nutritive benefit.

So what are your alternatives?

Of course, when it comes to adding flavour, there are a number of alternatives that can be just as tasty and even healthier than using excessive amounts of salt.

Garlic and ginger provide a sharp flavour and aroma that will enhance any meal as will lemon – try the lemon trick before you add salt, it can really add flavour.

Many herbs such as rosemary, basil, sage, thyme, dill and coriander are delicious aromatic additions, whilst spices such as cinnamon, nutmeg, cardamom, cumin, paprika, turmeric and chilli infuse pungent flavours to both savoury and sweet dishes.

The bottom line is this: if you’re eating mainly unprocessed whole foods, it is not a problem to add some salt to your meals, as long as your overall intake is moderate. If your food stops tasting good despite the salt you’re adding, it’s likely that your taste buds have become accustomed to a high salty taste and have become less receptive to other flavours. So cut back.

I originally wrote this article for HEALTHISTA and it has also appeared on the MailOnline

UPDATE NOVEMBER 2021

A new study; a first of its kind, has revealed surprising information about how the brain is affected by salt consumption.

When we eat salt, our body needs to control the amount that remains in the body very precisely; there are specific cells that detect how much salt is in the blood. The brain then senses the elevated amounts and consequently activates a series of mechanisms to bring the levels back down.

To do this, neurons in the brain are activated resulting in a rapid increase in blood flow to the area. Until now, research has been limited to the superficial areas of the brain but now, new research has focused on the deeper regions of the brain; the hypothalamus.

Researchers were surprised to find that instead of increased blood flow to these deeper regions, there was in fact a decrease in blood flow to the hypothalamus when the neurons were activated.

This response; reduced blood flow, is normally observed in diseases like Alzheimer’s or after a stroke. The response took place slowly and over a long period of time. In other words, the lack of blood flow can lead to tissue damage in the brain.

“When we eat a lot of salt, our sodium levels stay elevated for a long time. We believe the hypoxia is a mechanism that strengthens the neurons’ ability to respond to the sustained salt stimulation, allowing them to remain active for a prolonged period.”

The authors now intend to further research into how high blood pressure, as a result of excessive salt intake may affect the brain.

1 Comment